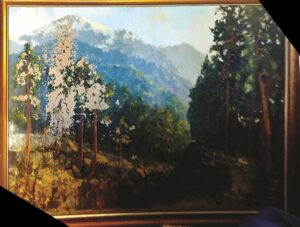

Collector’s Gallery: Sun-Bleached Painting

The location of this reader’s painting exposed it to the sun.

Q: This picture was near the front door, and the sun bleached part of the picture. The name of the artist is at the bottom right of the picture, but I can’t figure out who it is. Picture is 64” height and 103” wide. I wondered if you can figure out who the artist is and if it has any value. Thanks.

A: Your very large painting appears to be signed “FAVS” followed by a crosshair. Unfortunately, I have been unable to locate any artist that signed their paintings with such a signature and symbol. Your painting appears to be one of those that are mass-produced, which are commonly called factory art, decor paintings, hotel art, or commercial art, whose sole purpose is to add color to the space above a couch or bed. A photograph of the back, especially the stretcher and the method by which the canvas is attached to the stretcher, would have provided a great deal more information.

Your painting, however, provides us with an opportunity for a brief discussion on painting restoration. The painting itself is in disastrous condition, with most of the original focus, the trees, having flaked off. Even if this had been a good painting, the condition would decrease the value by more than ninety percent. Restoration would be incredibly costly and not worth the expense due to the amount and portions of the painting that are currently missing; the trees are the main focus of this painting, and they are all gone. Paintings should not be exposed to direct sunlight, nor hung over fireplaces that are often used.

A painting is considered “original’ if restoration is minimal, reversible, and strictly limited to areas of damage—such as in-painting for spots of loss, cleaning, or stabilizing the structure—without altering the artist’s intent or overly supplementing surviving material. Professional guidelines require that any added materials can be removed in the future, and all interventions should be documented to distinguish between the original and restored sections.

If extensive intervention replaces or alters a substantial portion of the work, especially more than half of the surface, the authenticity and value become compromised; the work risks being viewed as a collaboration between artist and restorer rather than a true original. The line is subjective, but when restoration dominates visually or structurally, experts, museums, and the market may no longer consider the painting “original.”

As always, there is nothing like hands-on examination. If this is a mass-produced piece, the value might only be in the frame.

Our guest appraiser is Dr. Anthony Cavo, a certified appraiser of art and antiques and a contributing editor to Kovels Antique Trader. Cavo is also the author of Love Immortal: Antique Photographs and Stories of Dogs and Their People.

Do you have a question for Collector’s Gallery? Send your question and photos via e-mail to ATNews@aimmedia.com. Please include as much pertinent information about your item as possible, including size, condition, history and anything else that might help in identifying and valuing your item.

You May Also Like:

Paws, Paint, and Prestige: Canine Art Fetches Top Bids at Freeman’s | Hindman

Arnold Rothstein

Arnold Rothstein