Identification Guides

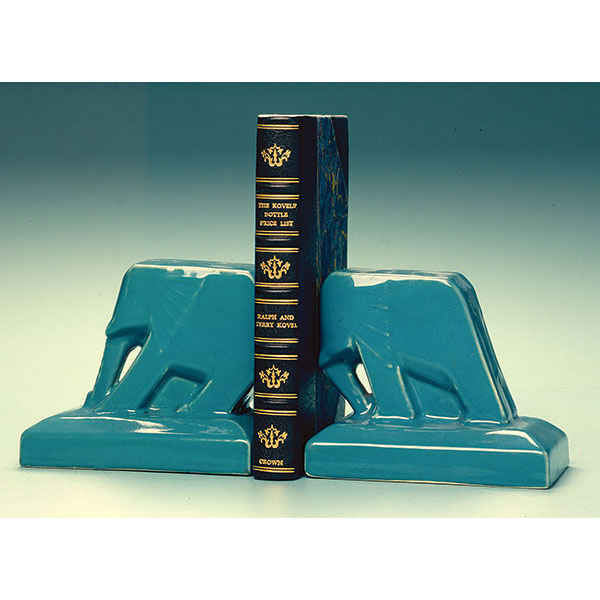

American Art Pottery

Art pottery was made in America from the late 1870s to the 1950s. The term "art pottery" can have several meanings. To the scholar and researcher, it is pottery that was handmade or primarily handmade and produced in the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement before the 1940s. The company that produced art pottery may also have made industrial or florist wares at the same time.

Collectors define art pottery a little differently. For them, the term refers to any pottery made by companies that produced art pottery during the 1876-1950 era. Sometimes it includes commercial and florist wares like those by Roseville; sometimes it includes studio potters’ work from the 1920s through the 1940s. California potteries were founded much later than those on the East Coast, so collectors sometimes call pottery made in the West as late as the 1950s “art pottery.”

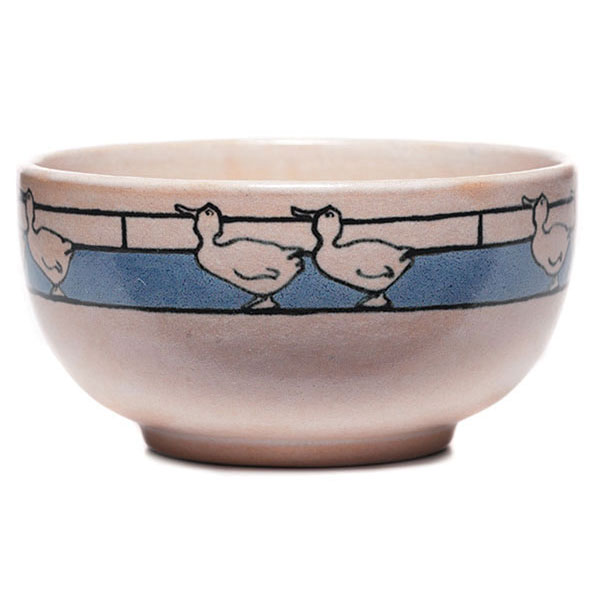

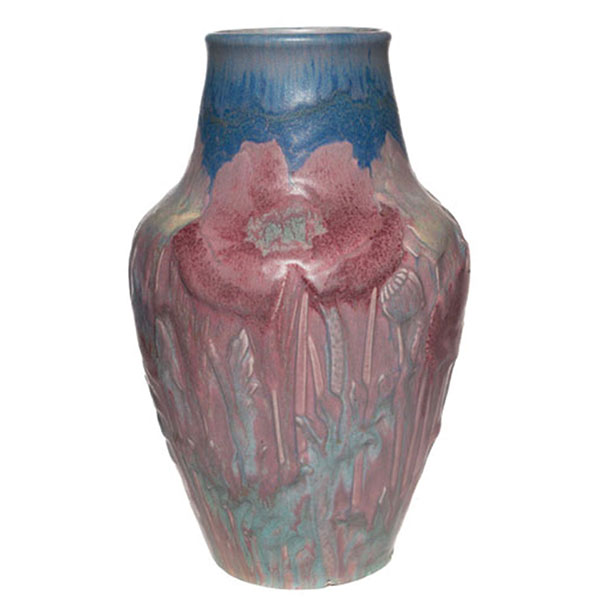

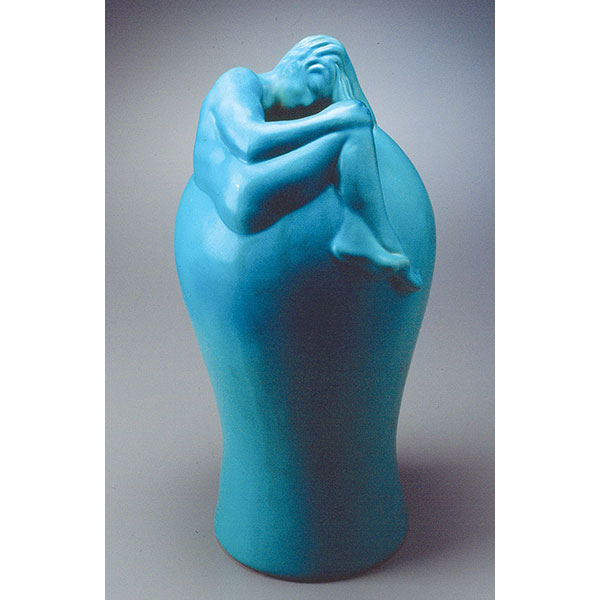

Art pottery was hand-thrown and hand-decorated. It was made to be a thing of beauty, not just a commercial, utilitarian vessel. Later pieces, also considered part of the art pottery movement, were made with underglaze slip decoration, matte glaze, or high-gloss glaze, and with carved, molded, or applied decoration. Many of the art potteries started as one-man or one-woman operations and then grew to become large successful financial ventures with hundreds of employees.

The first American art pottery was made soon after the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. The latest French and British ceramic designs and techniques were on display in Philadelphia. Haviland and Company exhibited pottery with underglaze designs made at its Auteuil studio near Paris. Doulton and Company of London displayed salt-glazed stoneware and faience with underglaze designs. The exotic, unfamiliar ceramics exhibited by the Japanese were another important influence. The critics considered the American pieces on display—primarily porcelain and white ware by potteries like Ott and Brewer, New York City Pottery, Union Porcelain Works, and Laughlin Brothers Pottery— inferior, not as artistic or imaginative as the work by the English, French, and Japanese. The Exposition’s Women’s Pavilion showed off the pottery and other art done by women working in the United States. A display of ceramics by a group of women working in Cincinnati, Ohio, was included. The women used mineral painting over the glaze, a technique that was new in America. The critics were impressed, not by the artistic quality of the pottery but by the possibility that women could be employed making ceramics for sale. Many of the art potteries started in the next 50 years were established to teach women a marketable skill so they could support themselves in an “honorable” job.

America's art pottery movement began at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Many artists who eventually worked for art potteries were inspired by work displayed at the exhibition. Mary Louise McLaughlin, an amateur potter from Cincinnati, saw the French Haviland pottery and the next year, after experimenting, she began making pottery with similar decorations. Hugh Robertson was inspired by sang de boeuf-glazed (red) pieces in the Chinese exhibit. Susan Frackelton of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, won a medal for a piece at the Centennial. William Long, a druggist from Steubenville, Ohio, who started Lonhuda Pottery in 1892, became interested in making pottery because of displays in Philadelphia. The unfamiliar designs seen in the Chinese and Japanese exhibits led to the creation of exotic decorations by American potters.

Others soon discovered this new style. In 1880 Cincinnati potter Maria Longworth Nichols founded the Rookwood Pottery (1880–1967), which became a successful commercial enterprise. Other Cincinnati-area potteries included Cincinnati Art Pottery Company (1879–1891), Matt Morgan Art Pottery (1883–1884), and Avon Pottery (1886–1888). Some of the potters who trained at Rookwood left to found other companies, such as the Van Briggle Pottery (1901–present) of Colorado Springs, Colorado; Pauline Pottery (1883–1893) of Chicago, Illinois, and Edgerton, Wisconsin; and Valentien Pottery (1911–1914) of San Diego, California.

Other firms that took advantage of the natural assets and potters available in Ohio included the Roseville Pottery (1892–1954), Weller Pottery (1872–1948), Lonhuda Pottery (1892–1895), and Cowan Pottery (1913–1931). At the same time, potteries were operating in other parts of the country. New England potters had seen the same Haviland pieces at the Centennial, and soon art potteries like Chelsea Keramic Art Works (1875–1889), Dedham (1895–1943), Volkmar (1879–1911), and Low Art Tile Works (1877–1902) were founded.

Eventually the art pottery movement spread to all parts of the United States. George Ohr’s Biloxi pottery in Biloxi, Mississippi, made Ohr’s unique style of crumpled vases. Newcomb Pottery (1895–1939) in New Orleans perfected a matte glazed ware with carved stylized floral decoration. Grueby (1894–1911) pottery, made in Boston, was decorated with a matte green glaze that became so popular it was copied at lower prices and the company was forced to close. Other art potteries opened in Michigan, Illinois, and California.

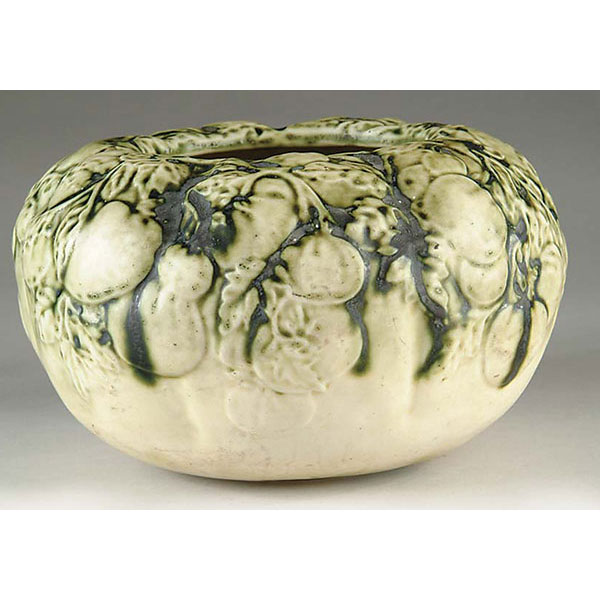

Some companies found the problems of making a high-quality artistic ware too difficult and simply closed. Others kept making more and better designs while enlarging their plants. By the 1920s many of the firms, especially in Ohio, were making both art pottery and commercial-quality wares to sell to florists and gift shops for reasonable prices. Gradually the quality of the work suffered as pricing became more important, and by the late 1920s most of the firms that had produced art pottery had either closed or discontinued their art lines. Crafts people who wanted to make pottery worked alone in small shops and became known as “studio potters.”

Collectors have expanded the meaning of art pottery to include not only the manmade artistic pottery made from 1876 to the 1950s, but also some commercial and florist wares made during those years. These vases were made by Brush Pottery.